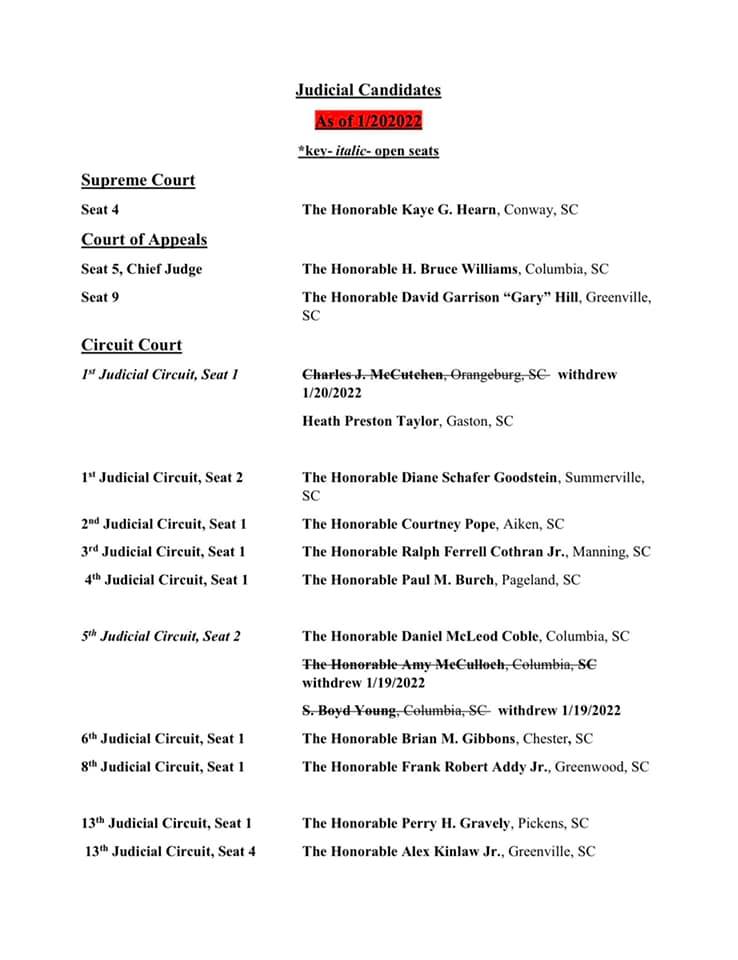

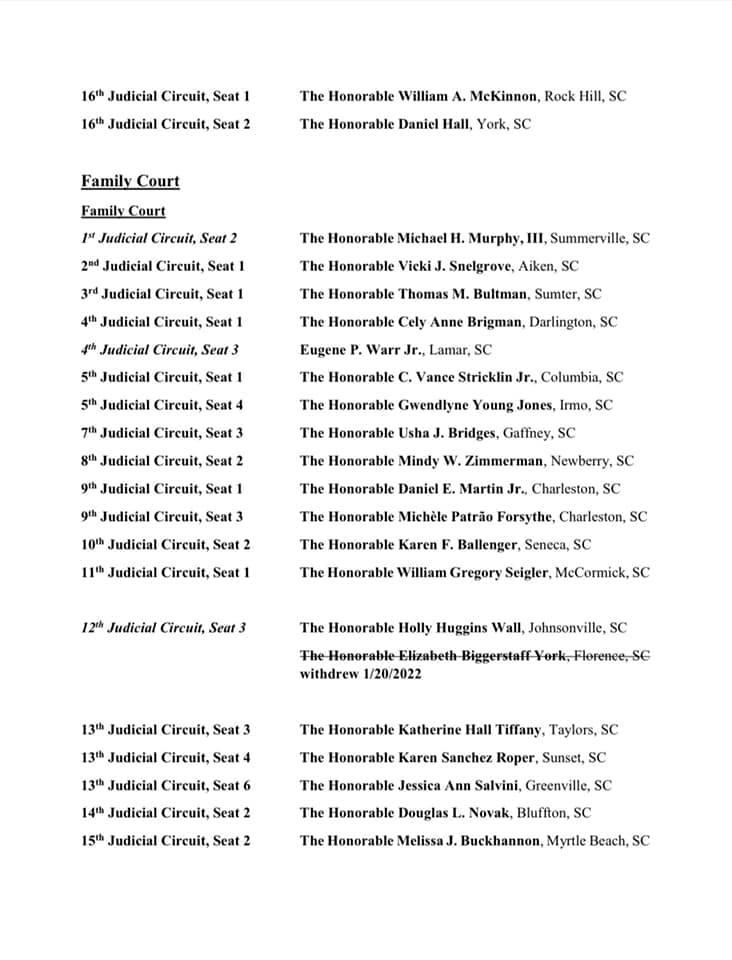

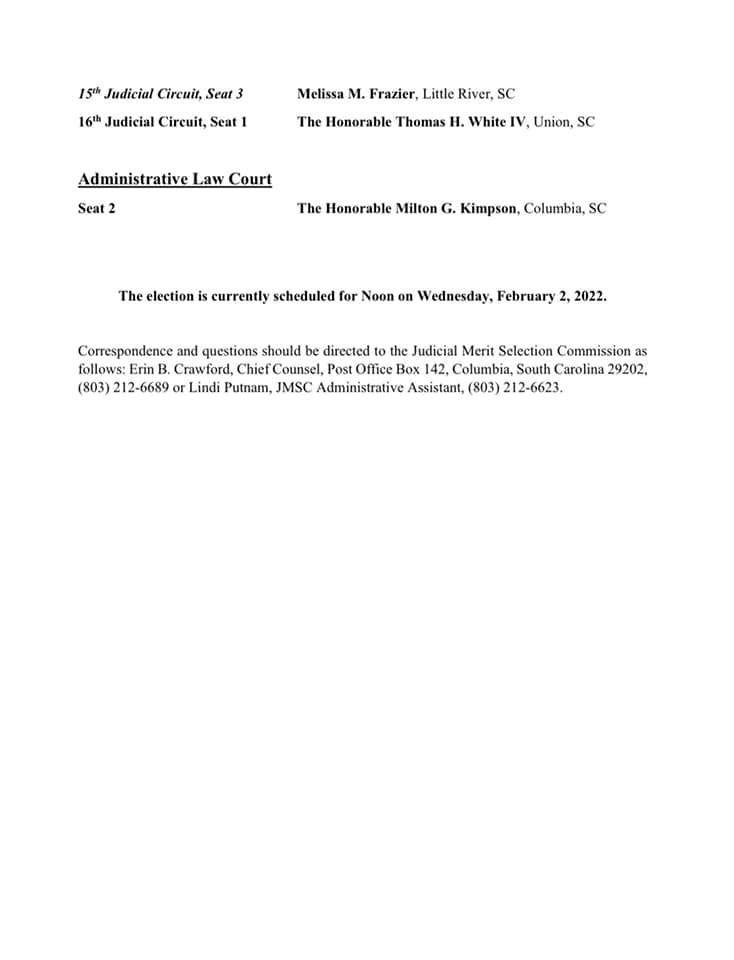

1.20.22 UPDATE: Ahead of next month’s judicial elections, including for one seat on the state Supreme Court and Administrative Law Court, and many on the Court of Appeals, circuit court, and family court, enough candidates have dropped out that there are NO contested seats left. Lawmakers are left to choose from one candidate for each judicial seat. To see the full list of candidates and open judicial seats, scroll to the bottom.

***

Prospective South Carolina judges are currently undergoing a legislatively controlled screening process with the hope of filling one of many vacancies on several powerful state courts.

But an analysis of the selection process reveals serious and unavoidable conflicts of interest that threaten the integrity of our judicial system. Who is in charge, why does it matter, and what needs to change?

An unpopular, problematic method

South Carolina is one of only two states where their legislatures play primary roles in electing judges. The Legislature – the same body writing the laws on which judges are expected to rule – fills vacancies on the state Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, circuit court, family court, and Administrative Law Court. While the appointment of magistrate and master-in-equity judges is also subject to legislative control, though in different ways, this report is focused primarily on those elected by lawmakers.

Long before they make it to election day, judicial candidates are being evaluated by their legislative employers. A ten-member Judicial Merit Selection Commission (JMSC) must first screen and nominate judges before they can be elected. The commission is appointed by just three lawmakers: the House speaker (five appointments); the Senate president (two appointments); and the Senate Judiciary Committee chairman (three appointments). Six of 10 commissioners must be lawmakers themselves.

The process begins with a closed-door investigation of each of the candidates that have applied. Here, the commission has complete discretion to utilize documents from any state agency, law enforcement body, or court administration to inform its decision. It may also subpoena witnesses for testimony. Records obtained during the investigation must be kept confidential and destroyed once finished.

Following the investigation, a series of hearings are scheduled to consider whether the judicial applicants are qualified. Each candidate must appear before the commission, answering questions generally involving their professional experience, desires for being a judge, or responding to public complaints filed against them. The commission may also interview anyone, including candidates, during a closed-door executive session.

The screening process is not exactly friendly to the public. Commission hearings are neither streamed nor recorded, meaning interested citizens must attend in person – an inconvenience especially for those outside Columbia. Anyone wishing to speak is required to do so under oath, and must submit a written statement of their proposed testimony at least two weeks before the hearing. Even then, the commission may deny the request.

The commission’s biggest responsibility, of course, is nominating candidates for election by the General Assembly. It may nominate up to three for each vacant judicial seat. Simply put, a candidate who is on bad terms with the commission, especially with some of its more influential members, will not become a judge in South Carolina.

After nominees have been announced and an official report released, hopeful judges can begin seeking a pledge for votes directly from lawmakers. In some ways, this period is as, if not more, important than the election itself. Nominees unable to secure enough votes will often drop out before election day. Election outcomes, as a result, can be very predictable – especially for nominees that receive the support of legislative leadership.

Though higher-level judges are elected in a joint session of the General Assembly, state law only requires that a candidate receive a simple majority of votes to win election. Given that House membership far outnumbers the Senate (124-46), it is possible that the House, controlled by the speaker, could elect a judge without a single vote from the other chamber. Even in Virginia, where judges are elected by the Legislature, judges must receive enough votes from both chambers.

Who do our judges really serve?

South Carolinians will never have independent courts when the selection of judges is dominated by a competing branch of government. Under this system, a judge who challenges legislative power – a fundamental responsibility – is putting his or her chances of reelection at risk.

This is complicated by the many personal relationships between legislators and the judges they select. Those on the screening commission will often know candidates personally or have appeared before them in court. A review of JMSC members found that every lawmaker on the commission is an attorney, meaning they have not only a political interest, but a professional stake in each judge’s nomination.

Unfortunately, these conflicts of interest are not confined to the screening committee. According to the South Carolina Bar, attorneys make up roughly 30% of the General Assembly. With that many lawyers being spread so wide across the state, it is unlikely there are many courtrooms in South Carolina unaffected by legislators’ influence.

This dynamic creates a dangerously uneven playing field – one that favors the Legislature at-large when the validity of a law is challenged, but also one against every citizen or business when faced against a client represented by a lawmaker. It threatens the entire concept of judicial independence.

It is no coincidence, then, that legislative elections are used in just two states. Instead of existing as co-equal branches of government, where the judiciary serves as check on legislative power, South Carolina judges have become dominated by their employer. This isn’t just our position. The influential political theorist, Montesquieu, wrote in The Spirit of Laws (1748):

“There is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator …”

This is not to suggest that the other branches don’t have a role in the selection process – that is unavoidable if judges are to be spared from chaos of popular elections. While understandably tempting, judges must be concerned first with the law, not campaigns, fundraising and the shifting needs of voters.

True reform

For these reasons, reforming South Carolina’s judicial selection process is top among our recently published Eight Reforms. Judges should be nominated by the governor with Senate confirmation, similar to the federal model. The JMSC should be abolished. No lawmaker, other than the senators voting to approve or reject the governor’s nominee, should have direct control over the selection process. These changes would dramatically limit the legislative influence on our courts and ensure a more independent judiciary.

Changing the selection process would require amending the state Constitution, which takes a two-thirds vote by each chamber, then approval by a majority of voters. The approved amendment must also be ratified by both chambers. If anything, these hurdles only highlight the need for this process to begin sooner rather than later. Fortunately, the selection of powerful local magistrate judges – controlled primarily by small groups of state senators – can be fixed by simply changing state law.

If lawmakers are serious about addressing one of South Carolina’s most urgent and consequential government issues, these reforms must be a priority when they return next year.

[…] Fixing the process by which judges are selected is our number one reform. To read more about this issue, click here. […]

[…] Fixing the process by which judges are selected is our number one reform. To read more about this issue, click here. […]